Type 2 diabetes is a social disease, not a clinical one. Before you respond, “This is nonsense,” hear me out. Yes, I am aware people develop type 2 diabetes when the cells in their body become resistant to insulin and the pancreas can’t produce enough insulin to manage their blood sugar levels. But what are the societal conditions that contribute to developing this disease?

Most of us know the risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes. Some, like age and ethnicity, are unavoidable. But many, called lifestyle factors, can be modified: obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, sedentary behavior and lack of exercise, smoking and heavy drinking. Risk factors don’t appear in a vacuum. Upstream causes, called Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) are the behaviors and conditions in places where vulnerable people live, learn, work, and play. These include: housing, including living in areas where outdoor exercise is unsafe; food insecurity and living in food deserts with limited access to affordable, healthy food; carrying the stress of systemic racism; inferior education, unreliable transportation and living in isolation with little connection to other people. These contribute to a wide range of health risks and when taken together, it’s no surprise that lower-income people have higher rates of diabetes and shorter lifespans.

Doctors and health researchers agree on how to lower your risk for type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases: Eating healthy food, such as vegetables, fruit, fish, lean meats, beans, nuts and seeds; the time, safety and space to exercise and spend time outdoors; healthy avenues to manage stress; and access to quality healthcare when you need it. People working long hours at low-wage jobs to make ends meet have little time to exercise and may not be able to reach a safe place to spend time outdoors and in nature, which research shows lowers stress levels, boosts mood and is good for mental and physical health. Many low-wage workers lack the health benefits that pay for preventative medicine, such as an annual physical, where early signs of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and risk for diabetes could be detected and treated. SDoH are inseparable from historic, systemic racism, persistent racial inequities and intergenerational trauma. Just one example of this: American Indian/Alaska Native and Black women are two- to three-times more likely to die from a pregnancy related cause than white women in the United States, reports the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

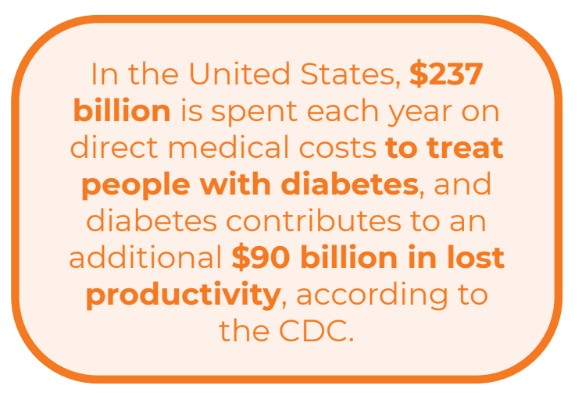

In the United States, $237 billion is spent each year on direct medical costs to treat people with diabetes, and diabetes contributes to an additional $90 billion in lost productivity, according to the CDC. Out of every $4 in U.S. health care costs, $1 is spent on caring for people with diabetes. Taxpayers are footing the majority of that bill, since 61% of diabetes costs are for adults 65 and older, which is mainly paid by Medicare.

We can’t just blow it all up and stop managing and treating diabetes, since we would only be punishing those people who suffer from the disease, many as a consequence of life’s lottery. But couldn’t the health industry better use its resources to strategically reallocate funds over time to address the causes of SDoH and invest in companies and organizations that work to tackle SDoH and inequities? This includes community health organizations and groups that can reach members in their communities and work to close the gaps between the vulnerable and the privileged.

Wouldn’t this deliver far higher value to consumers, taxpayer-funded health benefit plans, (Medicare and Medicaid) and to health insurers, since preventing health problems is cheaper than treating them? SDoH and equity are buzz words du jour in healthcare, but in this author’s opinion, until there is a sustained shift to investing in the reasons people have obesity, lack access to affordable, healthy food, don’t exercise and cope with stress with cigarettes and alcohol, the same patterns will persist and grow, not just in diabetes rates but in many other prevalent diseases, including heart disease, the nation’s number 1 killer.

Thoughts?

[Disclaimer: I am the chief medical officer for a community health company, Wider Circle, that works upstream to tackle the SDoH, so you can take this with a pinch of salt.]